American Historical Review 1934 39#2 Pp 219-231 Pp 219-2314

Seal of the American Historical Association | |

| Formation | 1884 (1884) |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

| Website | world wide web |

The American Historical Association (AHA) is the oldest professional association of historians in the U.s.a. and the largest such organization in the world. Founded in 1884, the AHA works to protect academic freedom, develop professional standards, and back up scholarship and innovative pedagogy. It publishes The American Historical Review four times a yr, with scholarly articles and book reviews. The AHA is the major organisation for historians working in the United States, while the Arrangement of American Historians is the major system for historians who report and teach near the The states.

The grouping received a congressional lease in 1889, establishing information technology "for the promotion of historical studies, the collection and preservation of historical manuscripts, and for kindred purposes in the interest of American history, and of history in America."

Current activities [edit]

As an umbrella organisation for the discipline, the AHA works with other major historical organizations and acts as a public abet for the field. Within the profession, the association defines ethical behavior and all-time practices, especially through its "Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct".[i] The AHA too develops standards for good exercise in teaching and history textbooks, but these have limited influence.[ii] The association mostly works to influence history policy through the National Coalition for History.[three] [four]

The clan publishes The American Historical Review, a major periodical of history scholarship covering all historical topics since ancient history[5] and Perspectives on History, the monthly news magazine of the profession.[6] In 2006 the AHA started a blog focused on the latest happenings in the broad subject area of history and the professional practice of the craft that draws on the staff, research, and activities of the AHA.[7]

The clan's annual meeting[8] each January brings together more than 5,000 historians from around the U.s. to discuss the latest inquiry and talk over how to exist better historians and teachers. Many affiliated historical societies agree their annual meetings simultaneously. The association's web site offers all-encompassing information on the current state of the profession,[9] tips on history careers,[10] and an all-encompassing annal[11] of historical materials (including the 1000.I. Roundtable series),[12] a series of pamphlets prepared for the War Department in World State of war II.

The clan also administers ii major fellowships,[13] 24 book prizes,[14] and a number of small research grants.[13]

History [edit]

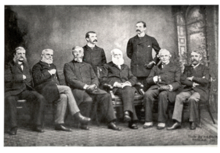

Executive officers of the American Historical Association at the time of the association's incorporation past Congress, photographed during their annual meeting on December thirty, 1889, in Washington, D.C. Seated (L to R) are William Poole, Justin Winsor, Charles Kendall Adams (President), George Bancroft, John Jay, and Andrew Dickson White, Continuing (L to R) are Herbert B. Adams and Clarence Winthrop Bowen

The early leaders of the clan were mostly gentlemen with the leisure and means to write many of the great 19th-century works of history, such as George Bancroft, Justin Winsor, and James Ford Rhodes. Withal, every bit sometime AHA president James J. Sheehan points out,[xv] the association always tried to serve multiple constituencies, "including archivists, members of land and local historical societies, teachers, and amateur historians, who looked to information technology - and non e'er with success or satisfaction - for representation and support." Much of the early work of the association focused on establishing a common sense of purpose and gathering the materials of research through its Historical Manuscripts and Public Athenaeum Commissions.[ citation needed ]

Publication standards [edit]

From the starting time, the association was largely managed by historians employed at colleges and universities, and served a critical office in defining their interests every bit a profession. The association'due south first president, Andrew Dickson White, was president of Cornell University, and its beginning secretary, Herbert Baxter Adams, established one of the start history Ph.D. programs to follow the new German seminary method at Johns Hopkins University. The clearest expression of this academic impulse in history came in the development of the American Historical Review in 1895. Formed by historians at a number of the about important universities in the United States, it followed the model of European history journals. Under the early editorship of J. Franklin Jameson, the Review published several long scholarly articles every consequence, just afterwards they had been vetted by scholars and approved by the editor. Each issue also reviewed a number of history books for their conformity to the new professional norms and scholarly standards that were taught at leading graduate schools to Ph.D. candidates. From the AHR, Sheehan concludes, "a junior scholar learned what it meant to exist a historian of a sure sort".

AHA and public history [edit]

Meringolo (2004) compares academic and public history. Unlike academic history, public history is typically a collaborative effort, does non necessarily rely on principal research, is more democratic in participation, and does non aspire to absolute "scientific" objectivity. Historical museums, documentary editing, heritage movements and historical preservation are considered public history. Though activities now associated with public history originated in the AHA, these activities separated out in the 1930s due to differences in methodology, focus, and purpose. The foundations of public history were laid on the heart basis betwixt academic history and the public audience by National Park Service administrators during the 1920s-30s.

The academicians insisted on a perspective that looked beyond particular localities to a larger national and international perspective, and that in practice it should be done forth modern and scientific lines. To that terminate, the clan actively promoted excellence in the area of inquiry, the clan published a series of annual reports through the Smithsonian Establishment and adopted the American Historical Review [xvi] in 1898 to provide early on outlets for this new make of professional person scholarship.

Establishing a national history curriculum [edit]

In 1896 the association appointed a "Committee of Vii" to develop a national standard for college admission requirements in the field of history. Before this fourth dimension, individual colleges defined their own entrance requirements. Afterward substantial surveys of prevailing teaching methods, emphases and curricula in secondary schools, the Committee published "The Study of History in Schools" in 1898.[17] Their study largely divers the way history would exist taught at the high schoolhouse level as a preparation for higher, and wrestled with bug about how the field should relate to the other social studies.[18] The Commission recommended 4 blocks of Western history, to be taught in chronological order—ancient, medieval and modern European, English, and American history and civil government—and brash that teachers "tell a story" and "bring out dramatic aspects" to make history come alive.[19]

[T]he educatee who is taught to consider political subjects in school, who is led to look at matters historically, has some mental equipment for a comprehension of the political and social problems that will face up him in everyday life, and has received practical preparation for social accommodation and for forceful participation in civic activities.... The student should see the growth of the institutions which surround him; he should see the piece of work of men; he should study the living concrete facts of the past; he should know of nations that have risen and fallen; he should run across tyranny, vulgarity, greed, benevolence, patriotism, self-sacrifice, brought out in the lives and works of men. And then strongly has this very thought taken concur of writers of civil government, that they no longer content themselves with a description of the government every bit it is, simply depict at considerable length the origin and evolution of the institutions of which they speak.[17]

The association also played a decisive role in lobbying the federal government to preserve and protect its own documents and records. After extensive lobbying by AHA Secretarial assistant Waldo Leland and Jameson, Congress established the National Athenaeum and Records Administration in 1934.

As the interests of historians in colleges and universities gained prominence in the association, other areas and activities tended to autumn past the wayside. The Manuscripts and Public Athenaeum Commissions were abandoned in the 1930s, while projects related to original inquiry and the publication of scholarship gained ever-greater prominence.

Recent developments [edit]

In recent years, the clan has tried to come to terms with the growing public history movement[ commendation needed ] and has struggled to maintain its condition as a leader among academic historians.[ citation needed ]

The clan started to investigate cases of professional misconduct in 1987, but ceased the endeavor in 2005 "because it has proven to be ineffective for responding to misconduct in the historical profession."[20]

Recent presidents [edit]

- 2013: Kenneth Pomeranz (Univ. of Chicago)

- 2016: Patrick Manning (University of Pittsburgh)

- 2017: Tyler Stovall (University of California, Santa Cruz)

- 2018: Mary Beth Norton (Cornell University)

- 2019: J. R. McNeill (Georgetown University)

- 2020: Mary Lindemann (University of Miami)

- 2021: Jacqueline Jones (University of Texas at Austin)[21]

- 2022: James H. Sweet (Academy of Wisconsin-Madison), elect

Selected awards [edit]

- for publications

- Herbert Baxter Adams Prize for the best book in European history

- George Louis Beer Prize for the best book in European international history since 1895

- Jerry Bentley Prize for the most outstanding volume on world history

- Albert J. Beveridge Award in American history for a distinguished book on the history of the United States, Latin America, or Canada, from 1492 to the present

- Paul Birdsall Prize for a major volume on European armed forces and strategic history since 1870

- James Henry Breasted Prize for the best book in any field of history prior to Advertizement thousand

- John H. Dunning Prize for the most outstanding book on The states history

- John One thousand. Fairbank Prize for the best book on E Asian history since 1800

- Morris D. Forkosch Prize for the all-time book in the field of British history since 1485

- Leo Gershoy Award for the best book in the fields of 17th and 18th-century western European history

- Friedrich Katz Prize for the best book in Latin American and Caribbean history

- James A. Rawley Prize for the best book that explores the integration of Atlantic worlds before the 20th century

- for professional person distinction

- James Harvey Robinson Prize for the teaching assistance that has fabricated the most outstanding contribution to the instruction and learning of history in whatever field

- Herbert Feis Award for distinguished contributions to public history

- Honor for Scholarly Distinction to senior historians for lifetime achievement

Past presidents [edit]

Presidents of the AHA are elected annually and give a president's address at the annual meeting:

- Andrew Dickson White (1884, 1885)

- George Bancroft (1886)

- Justin Winsor (1887)

- William Frederick Poole (1888)

- Charles Kendall Adams (1889)

- John Jay (1890)

- William Wirt Henry (1891)

- James Burrill Angell (1892–1893)

- Henry Adams (1893–1894)

- George Frisbie Hoar (1895)

- Richard Salter Storrs (1896)

- James Schouler (1897)

- George Park Fisher (1898)

- James Ford Rhodes (1899)

- Edward Eggleston (1900)

- Charles Francis Adams, Jr. (1901)

- Alfred Thayer Mahan (1902)

- Henry Charles Lea (1903)

- Goldwin Smith (1904)

- John Bach McMaster (1905)

- Simeon East. Baldwin (1906)

- J. Franklin Jameson (1907)

- George Burton Adams (1908)

- Albert Bushnell Hart (1909)

- Frederick Jackson Turner (1910)

- William Milligan Sloane (1911)

- Theodore Roosevelt (1912)

- William A. Dunning (1913)

- Andrew C. McLaughlin (1914)

- H. Morse Stephens (1915)

- George Lincoln Burr (1916)

- Worthington C. Ford (1917)

- William R. Thayer (1918–1919)

- Edward Channing (1920)

- Jean Jules Jusserand (1921)

- Charles H. Haskins (1922)

- Edward P. Cheyney (1923)

- Woodrow Wilson (1924, died earlier completing his term every bit president)

- Charles M. Andrews (1924, 1925)

- Dana C. Munro (1926)

- Henry Osborn Taylor (1927)

- James H. Breasted (1928)

- James Harvey Robinson (1929)

- Evarts Boutell Greene (1930)

- Carl Lotus Becker (1931)

- Herbert Eugene Bolton (1932)

- Charles A. Bristles (1933)

- William E. Dodd (1934)

- Michael I. Rostovtzeff (1935)

- Charles McIlwain (1936)

- Guy Stanton Ford (1937)

- Laurence M. Larson (1938)

- William Scott Ferguson (1939)

- Max Farrand (1940)

- James Westfall Thompson (1941)

- Arthur M. Schlesinger (1942)

- Nellie Neilson (1943)

- William 50. Westermann (1944)

- Carlton J. H. Hayes (1945)

- Sidney B. Fay (1946)

- Thomas J. Wertenbaker (1947)

- Kenneth Scott Latourette (1948)

- Conyers Read (1949)

- Samuel E. Morison (1950)

- Robert Livingston Schuyler (1951)

- James Yard. Randall (1952)

- Louis Gottschalk (1953)

- Merle Curti (1954)

- Lynn Thorndike (1955)

- Dexter Perkins (1956)

- William L. Langer (1957)

- Walter Prescott Webb (1958)

- Allan Nevins (1959)

- Bernadotte E. Schmitt (1960)

- Samuel Flagg Bemis (1961)

- Carl Bridenbaugh (1962)

- Crane Brinton (1963)

- Julian P. Boyd (1964)

- Frederic C. Lane (1965)

- Roy F. Nichols (1966)

- Hajo Holborn (1967)

- John 1000. Fairbank (1968)

- C. Vann Woodward (1969)

- R. R. Palmer (1970)

- David M. Potter (1971, died before completing his term every bit president)

- Joseph R. Strayer (1971)

- Thomas C. Cochran (1972)

- Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (1973)

- Lewis Hanke (1974)

- Gordon Wright (1975)

- Richard B. Morris (1976)

- Charles Gibson (1977)

- William J. Bouwsma (1978)

- John Hope Franklin (1979)

- David H. Pinkney (1980)

- Bernard Bailyn (1981)

- Gordon A. Craig (1982)

- Philip D. Curtin (1983)

- Arthur S. Link (1984)

- William H. McNeill (1985)

- Carl N. Degler (1986)

- Natalie Zemon Davis (1987)

- Akira Iriye (1988)

- Louis R. Harlan (1989)

- David Herlihy (1990)

- William E. Leuchtenburg (1991)

- Frederic East. Wakeman Jr (1992)

- Louise A. Tilly (1993)

- Thomas C. Holt (1994)

- John H. Coatsworth (1995)

- Caroline Walker Bynum (1996)

- Joyce Appleby (1997)

- Joseph C. Miller (1998)

- Robert Darnton (1999)

- Eric Foner (2000)

- Wm. Roger Louis (2001)

- Lynn Chase (2002)

- James M. McPherson (2003)

- Jonathan Spence (2004)

- James J. Sheehan (2005)

- Linda Thousand. Kerber (2006)

- Barbara Weinstein (2007)

- Gabrielle M. Spiegel (2008)

- Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (2009)

- Barbara Metcalf (2010)

- Anthony Grafton (2011)

- William Cronon (2012)

- Kenneth Pomeranz (2013)

- January Due east. Goldstein (2014)

- Vicki L. Ruiz (2015)

- Patrick Manning (2016)

- Tyler Stovall (2017)

- Mary Beth Norton (2018)

- J. R. McNeill (2019)[22]

- Mary Lindemann (2020)

- Jacqueline Jones (2021)

Affiliated societies [edit]

- American Catholic Historical Association

- Coordinating Council for Women in History

- Conference on Latin American History

- National Council on Public History

- Oral History Clan

- Society for History in the Federal Authorities

- Society for Medieval Feminist Scholarship

- Society for Military History

- Gild of Architectural Historians

- World History Association

See too [edit]

- Bibliographical Gild of America

- List of American historians

References [edit]

- ^ "Statement on Standards of Professional Behave (updated 2011)".

- ^ "Instruction & Learning - AHA".

- ^ "National Coalition for History".

- ^ "Advocacy with the National Coalition for History". AHA. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "American Historical Review - AHR".

- ^ "Perspectives on History - AHA".

- ^ "AHA Today". American Historical Association.

- ^ "Almanac Meeting - AHA".

- ^ "Data on the History Profession".

- ^ "Jobs & Professional Development - AHA".

- ^ "AHA History and Archives - AHA".

- ^ "GI Roundtable Serial".

- ^ a b "AHA Grants and Fellowships".

- ^ "AHA Awards and Prizes".

- ^ Sheehan, James J. (Feb 2005). "The AHA and Its Publics, Part I". historians.org. American Historical Association. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- ^ http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/toc/ahr/current [ dead link ]

- ^ a b "The Study of History in Schools (1898)".

- ^ Orrill, Robert; Shapiro, Linn (ane June 2005). "From Bold Beginnings to an Uncertain Future: The Discipline of History and History Instruction". The American Historical Review. 110 (three): 727–751. doi:10.1086/ahr.110.3.727.

- ^ Ronald W. Evans (one January 2004). The Social Studies Wars: What Should Nosotros Teach the Children?. Teachers College Printing. pp. 10–16. ISBN978-0-8077-4419-ii . Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ "Policy on Professional Division Adjudication of Complaints".

- ^ "AHA Council - AHA". www.historians.org.

- ^ "AHA Council". American Historical Association. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

Selected bibliography [edit]

- Alonso, Harriet Hyman. " Slammin' at the AHA." Rethinking History 2001 5(3): 441–446. ISSN 1364-2529 Fulltext in Ingenta and Ebsco. The theme of the 2001 annual meeting of the AHA, "Practices of Historical Narrative," attracted a diversity of panels. The article traces one such console from its conception to presentation. Taking the theme to center, the panelists created a "slam" (or reading) of narrative histories written by experienced historians, a graduate student, and an undergraduate educatee, and so opened the session to readings from the audience.

- American Historical Association Committee on Graduate Education. "We Historians: the Gilded Age and Across." Perspectives 2003 41(five): eighteen–22. ISSN 0743-7021 Surveys the state of the history profession in 2003 and points out that numerous career options exist for persons with a Ph.D. in history, although the traditional ideal of a university-level appointment for new Ph.D.s remains the chief goal of doctoral programs.

- Bender, Thomas, Katz, Philip; Palmer, Colin; and American Historical Association Committee on Graduate Pedagogy. The Didactics of Historians for the Twenty-First Century. U. of Illinois Press, 2004. 222 pp.

- Elizabeth Donnan and Leo F. Stock, eds. An Historian's Globe: Selections from the Correspondence of John Franklin Jameson, (1956). Jameson was AHR editor 1895–1901, 1905–1928

- Higham, John. History: Professional person Scholarship in America. (1965, 2d ed. 1989). ISBN 978-0-8018-3952-viii

- Meringolo, Denise D. "Capturing the Public Imagination: the Social and Professional person Place of Public History." American Studies International 2004 42(2–3): 86–117. ISSN 0883-105X Fulltext in Ebsco.

- Morey Rothberg and Jacqueline Goggin, eds., John Franklin Jameson and the Evolution of Humanistic Scholarship in America (3 vols., 1993–2001). ISBN 978-0-8203-1446-4

- Novick, Peter. That Noble Dream: The "Objectivity Question" and the American Historical Profession. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-521-35745-6

- Orrill, Robert and Shapiro, Linn. "From Bold Beginnings to an Uncertain Future: the Discipline of History and History Didactics." American Historical Review 2005 110(3): 727–751. ISSN 0002-8762 Fulltext in History Cooperative, University of Chicago Printing and Ebsco. In challenging the reluctance of historians to join the national debate over instruction history in the schools, the authors fence that historians should remember the leading role that the profession one time played in the making of school history. The AHA invented school history in the early on 20th century and remained at the forefront of Grand–12 policymaking until merely prior to Earth War II. However, it abandoned its long-continuing activist stance and allowed school history to be submerged inside the ill-defined, antidisciplinary domain of "social studies."

- Sheehan, James J. "The AHA and its Publics - Part I." Perspectives 2005 43(2): five–vii. ISSN 0743-7021

- Stearns, Peter N.; Seixas, Peter; and Wineburg, Sam, ed. Knowing, Didactics, and Learning History. New York U. Press, 2000. 576 pp. ISBN 978-0-8147-8142-5

- Townsend, Robert B. History's Babel: Scholarship, Professionalization, and the Historical Enterprise in the United States, 1880–1940. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-226-92393-2

- Tyrrell, Ian. Historians in Public: The Do of American History, 1890–1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-226-82194-8

External links [edit]

- Official website

finkelsteinalaing1940.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Historical_Association

Post a Comment for "American Historical Review 1934 39#2 Pp 219-231 Pp 219-2314"